Colour Management for Photographers 1

In a slight departure I am going to do a short series (I hope it will be short) on colour management. Why you ask? Well, I am not a spectral scientist, but I do have an extensive background in radio waves, of which of course light is such. I also have a number of years empirical knowledge when it comes to colour management in photography and it is probably the thing I find myself explaining most to the uninitiated. The motivation for putting it up here, on my blog, is that I have not found a concise one stop shop article (or series) on the internet that describes what you need to know. Sure there are probably millions of articles on the subject, but most deal with certain aspects, only skim the surface or delve to deeply into the science behind it. In the worst cases I have read a number of articles which are just plain incorrect, and for what is already a confusing subject for some, misinformation just confuses the situation. In fact it was upon reading an article recently that was so erroneous in its comments on colour management that I finally decided to write my own. If you want to explore the scientific details of colour, then this isn’t the article for you, and that is an interesting subject in its own right. If however you want to know enough to successfully colour manage your photographical workflow, this should provide a solid reference.

The article in its entirety is broken into four main sections, as shown below, however as an ongoing part of my attempts to keep posts to a digestible and punchy length, I will split these sections further, into parts. The first part of the first section is below; the remainder will be posted in the next week or two, at incremental periods. As each is released I will update the links below to provide a method of jumping between the parts.

Section One – Why Colour Manage

- Part One – In the context of the world we live in (below)

- Part Two – Why is our workflow important?

SectionTwo – All About Colour Spaces (coming soon)

Section Three - Capture, Display and Working Management (coming soon)

Section Four – Output Management (coming soon)

So, let’s get on with it before my word quota runs dry.

Section One - Why Colour Manage?

This is a double edged question. The first is why we need to colour manage in the context of the world we live in and the photographs we take, the second is why that then requires that we need to develop colour management in our photographic workflow, in order to satisfy the former. This first part will explore the former and the latter will be the subject of the next part.

Part One – In the context of the world we live in

As I am sure that anyone reading this with an interest in colour management will already know (being a photographer you ought to!), visible light is a mixture of various different colours, and when combined equally and completely they create white light. However, this theoretical complete and equal mixture rarely occurs, if ever naturally; and so we are left with slight imbalances where one part of the visible light spectrum is more dominant than the others. (It is possible that two parts of the spectrum can dominate, such as in mixed light scenarios, but that is another discussion.) To take an example, let’s talk about midday light. While this can vary too, it is normally accepted that the overall mix is quite evenly balances, with a slight bias towards the blue part of the spectrum. What this means is that we get generally neutral light (and even mixture of all colours) with a slight hint of blue. To show how this changes, think about the light towards the end of the day, in the golden hour. It comes as no surprise that it is known as the golden hour as the light has a golden hint to it, possible quite a strong bias. This is due to the fact that the bias in the mixture has moved to yellow, with more yellow in the mix the result is a yellowy or golden light.

Although it is not strictly anything to do with colour management, I want to discuss briefly about white balance, as it has a huge effect on the colour of light – and so is instrumental in why we colour manage. Unfortunately to talk of white balance, we also need to talk about how the colour of light is defined. There are misconceptions about this all over the net, so I think it is worthwhile delving into for a moment.

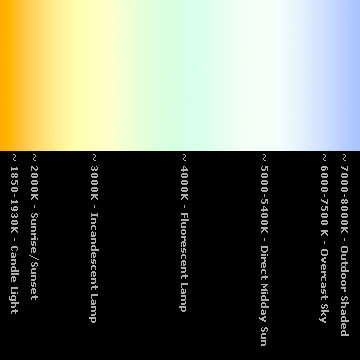

Let’s get the classification of light colour out of the way first. Everyone is most likely to have heard of the Kelvin scale, and it is this scale that is most popularly used to define the colour of a particular light. One of the errors I see most is getting the Kelvin scale the wrong way around, and there is a good reason for that, and it initially confused me too. So to provide a way of clarifying the Kelvin scale (where it applies to light colour), I will state how it is arrived at and why it is used. Ignoring why it is called the Kelvin scale and any references to absolute zero, (you can read about that elsewhere) the Kelvin scale is just another measure of heat, such as Celsius or Fahrenheit. If we were to take a solid bar of pure iron and heat it up, eventually it would start to glow, and if you have ever seen metal getting hotter and hotter you will know that it starts out with a red glow. As you increase the heat of the bar that glow will change to yellow, and as the heat is increased will turn white and if the temperature is increased further it will turn to a blue glow. I think you see where I am going with this!! If we want to find the “temperature” of a colour, we heat the iron bar until it matches that colour and note to what temperature (in Kelvin) the bar was to get the match. Thankfully we don’t have to do this, someone already did. Below are a few points of the Kelvin scale for colour.

The article in its entirety is broken into four main sections, as shown below, however as an ongoing part of my attempts to keep posts to a digestible and punchy length, I will split these sections further, into parts. The first part of the first section is below; the remainder will be posted in the next week or two, at incremental periods. As each is released I will update the links below to provide a method of jumping between the parts.

Section One – Why Colour Manage

- Part One – In the context of the world we live in (below)

- Part Two – Why is our workflow important?

SectionTwo – All About Colour Spaces (coming soon)

Section Three - Capture, Display and Working Management (coming soon)

Section Four – Output Management (coming soon)

So, let’s get on with it before my word quota runs dry.

Section One - Why Colour Manage?

This is a double edged question. The first is why we need to colour manage in the context of the world we live in and the photographs we take, the second is why that then requires that we need to develop colour management in our photographic workflow, in order to satisfy the former. This first part will explore the former and the latter will be the subject of the next part.

Part One – In the context of the world we live in

As I am sure that anyone reading this with an interest in colour management will already know (being a photographer you ought to!), visible light is a mixture of various different colours, and when combined equally and completely they create white light. However, this theoretical complete and equal mixture rarely occurs, if ever naturally; and so we are left with slight imbalances where one part of the visible light spectrum is more dominant than the others. (It is possible that two parts of the spectrum can dominate, such as in mixed light scenarios, but that is another discussion.) To take an example, let’s talk about midday light. While this can vary too, it is normally accepted that the overall mix is quite evenly balances, with a slight bias towards the blue part of the spectrum. What this means is that we get generally neutral light (and even mixture of all colours) with a slight hint of blue. To show how this changes, think about the light towards the end of the day, in the golden hour. It comes as no surprise that it is known as the golden hour as the light has a golden hint to it, possible quite a strong bias. This is due to the fact that the bias in the mixture has moved to yellow, with more yellow in the mix the result is a yellowy or golden light.

Although it is not strictly anything to do with colour management, I want to discuss briefly about white balance, as it has a huge effect on the colour of light – and so is instrumental in why we colour manage. Unfortunately to talk of white balance, we also need to talk about how the colour of light is defined. There are misconceptions about this all over the net, so I think it is worthwhile delving into for a moment.

Let’s get the classification of light colour out of the way first. Everyone is most likely to have heard of the Kelvin scale, and it is this scale that is most popularly used to define the colour of a particular light. One of the errors I see most is getting the Kelvin scale the wrong way around, and there is a good reason for that, and it initially confused me too. So to provide a way of clarifying the Kelvin scale (where it applies to light colour), I will state how it is arrived at and why it is used. Ignoring why it is called the Kelvin scale and any references to absolute zero, (you can read about that elsewhere) the Kelvin scale is just another measure of heat, such as Celsius or Fahrenheit. If we were to take a solid bar of pure iron and heat it up, eventually it would start to glow, and if you have ever seen metal getting hotter and hotter you will know that it starts out with a red glow. As you increase the heat of the bar that glow will change to yellow, and as the heat is increased will turn white and if the temperature is increased further it will turn to a blue glow. I think you see where I am going with this!! If we want to find the “temperature” of a colour, we heat the iron bar until it matches that colour and note to what temperature (in Kelvin) the bar was to get the match. Thankfully we don’t have to do this, someone already did. Below are a few points of the Kelvin scale for colour.

For interest, 5000K is 4726.85 degrees Celsius or 8540.33 degrees Fahrenheit. So if you were to take your iron bar and heat it to 4700 odd degrees C, it would be the same colour as midday sun light, give or take a bit.

But wait a minute, I hear many of you saying (OK I don’t, but anyway), that’s the wrong way around! On my camera, or in my RAW or editing software when I set a lower colour temperature, say 3000K I get a blue image, and when I set a high temperature, say 8000K I get a yellow image. And this is where the confusion I spoke of earlier comes in, and where many mistakes are made. The explanation is simple – if you apply a colour balance to a RAW image, for example, and you set it to 3000K, what you are saying is that the original scene was lit with 3000K light, which as we know now is yellowish, so what the software is trying to do is NEUTRALISE the light colour by adding the opposite part of the spectrum, blue. Aha, I hear you say (OK, again I don’t.). This really serves to confuse, but the easiest thing is to remember the true definition of the Kelvin scale being the iron bar getting hotter and hotter. The other thing which fuels the confusion is that we talk or warm and cool light, and just to be really difficult warm light has a yellow hue and cool light has a blue hue – but on the Kelvin scale blue is hotter than yellow, so how can blue be cool!!!! Well I am afraid you just have to live with that. Normally we view warm things are yellow/red, as generally they are – but when super heated they turn blue – we just don’t get to see that very often.

So now that we all understand the Kelvin scale, let’s get to white balance, which is usually measured in K (degrees Kelvin). The reason why we are talking about white balance, and hence the Kelvin scale, in an article on colour management is that it is that very colour of light we want to maintain through to output. The last thing we want is to work hard on taking photos in the right “quality” of light, and then to have part of that quality, the colour, changed when it is output to print for example. Which leads me to one more thing I would like to say abut white balance, which really, really has nothing to do with colour management, but I think it is worth stating anyway. Since the advent of digital photography the photographer has an almost infinite control over white balance, i.e getting the colour of the light captured to match what was there. In the good ol’ days photographers selected the appropriate film (mostly daylight balanced) and then if needed used filters to adjust for any bias. These were generally only used in extreme circumstances like neutralising incandescent or fluorescent lighting. The problem now is that with RAW, especially, the photographer needs to set the white balance himself, or use techniques and tools such as the expo disc etc, and most of these techniques are based around neutralising the light colour. That’s fine, if what you want to do is ensure that the subject appears as if it were lit with white light, such as product shots where getting the true colours is important, but if what you mean to do is capture the golden hour light, why on earth would you then try to neutralise it? Sounds logical, but there is so much emphasis on getting a neutral white balance in photography these days that a lot of people are spending time and money on loosing the quality of light that existed in the actual scene. Just something to take into consideration when selecting white balance – set the white balance to ensure that the light colour presented is as it was, or as you interpreted it; and remember that the Kelvin scale in your software is working in the opposite direction to reality, in order to compensate.

Up until now we have discussed only the relevance of colour management on white balance, or the colour of the light in the image. We are now going to talk briefly about the other, and more general, reason we need to colour balance; and that is the intrinsic colour of the subjects in the photograph. The two overlap, as the colour of the light lighting a scene effects all the colours in it (hence it’s important and why it was discussed at length above), but if we imagine for a moment a scene lit with perfectly white light, as may be done in a studio, then every part of the scene will still have its own colour. Flash tones are notorious for being troublesome in this area. Incorrect flesh tones will absolutely destroy and image, but to a certain degree so will every other error in colour representation. If there is a green apple in your scene, you would generally want the image to show that the apple was indeed green, and that the shade and brightness of green are accurate. Its actual shade of green will of course vary as the colour of the light is varied, but we still want that overall colour represented accurately.

So, to summarise this part, we need to colour manage our photographs to ensure the true colours as seen when captured (or as adjusted in our interpretation) are faithfully reproduced when we view the photograph on any medium, be that computer screen or print.

Of course, it is not as simple as making sure what we capture is colour managed, as from capture to print there are a number of steps along the way, such as camera, monitor and printer, all of which need to maintain the colours. And this is where that actual need for colour managing our workflow comes in, and will be the subject of the next part of Colour Management for Photographers.

nimbyref:070906a Photo: Lake Coniston Jetty, nimby. Canon 5D.:endnimby

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home